Measuring Academic Achievement of Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: Building Understanding of Alternate Assessment Scoring Criteria

NCEO Synthesis Report 50

Published by the National Center on Educational Outcomes

Prepared by:

Rachel Quenemoen • Sandra Thompson • Martha Thurlow

June 2003

Quenemoen, R., Thompson, S. & Thurlow, M. (2003). Measuring academic achievement of students with significant cognitive disabilities: Building understanding of alternate assessment scoring criteria(Synthesis Report 50). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide Web: http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/Synthesis50.html

Executive Summary

In this report, we compare and contrast the assumptions and values embedded in scoring criteria used in five states for their alternate assessments. We discuss how the selected states are addressing the challenge of defining successful outcomes for students with significant disabilities as reflected in state criteria for scoring alternate assessment responses or evidence and how these definitions of successful outcomes have been refined over time. The five states use different alternate assessment approaches, including portfolio assessment, performance assessment, IEP linked body of evidence, and traditional test formats. There is a great deal of overlap across the alternate assessment approaches, and they tend to represent a continuum of approaches as opposed to discrete categories.

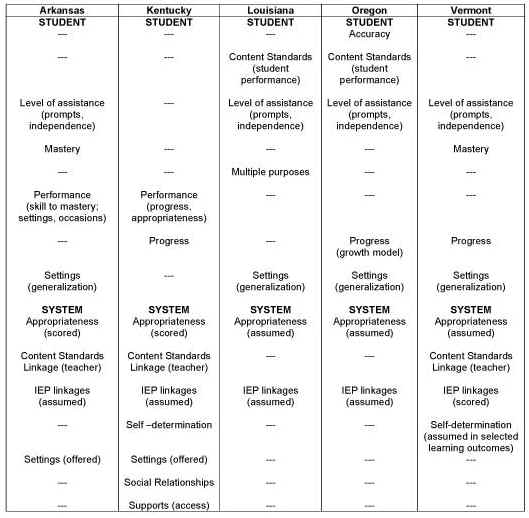

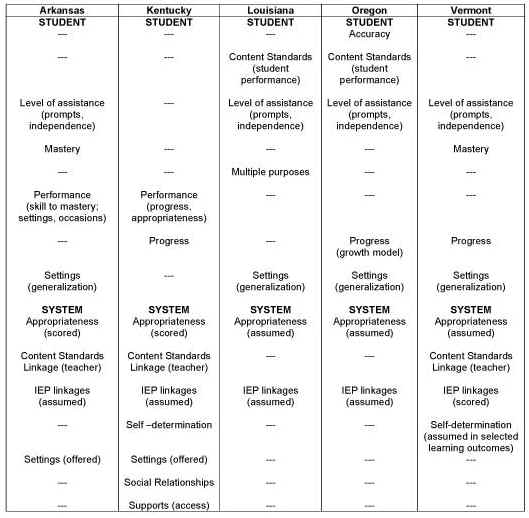

On surface examination, the scoring criteria used by the five selected states appear to be different from one another. State responses to the 2001 survey of state directors of special education (Thompson & Thurlow, 2001) suggested significant differences as well. Yet when the scoring elaborations and processes are examined closely, many similarities emerge. After careful analysis of how some assumptions are built into the instrument development or training processes, even more similarities emerge. The definitions and examples and the side by side examination of the criteria, the scoring elaborations, and the assumed criteria in the design of training materials and assessment format yield a surprising degree of commonality in the way these states define success for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Six criteria are included in all of the five states’ approaches in some way, either articulated or assumed. They include "content standards linkage," "independence," "generalization," "appropriateness," "IEP linkage," and "performance."

Three scoring criteria are very different across the five states’ approaches. They include "system vs. student emphasis," "mastery," and "progress." Two states also use additional criteria that no other state uses.The common criteria and differences in criteria across the five states described here do not reflect "right" or "wrong" approaches. Each of these five states has developed alternate assessment scoring criteria that reflect their best understanding of what successful outcomes are for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Since alternate assessments are a much more recent development than general assessments, the assumptions underlying them are still debated and discussed. These deliberations can sometimes feel frustrating for teachers, policymakers, and other stakeholders, but they are an important activity that helps a state develop an alternate assessment that reflects its educational values for students with significant cognitive disabilities.

We hope that many state personnel will have opportunities to read this report and will be prompted to carefully examine their own criteria, asking what each criterion means and how it is important to each student’s success. Alternate assessments are still very new, and taking the time for thoughtful reexamination is critical. We provide questions and recommendations you may find helpful as you work to ensure your alternate assessment reflects your state’s best understanding of successful outcomes for students with significant cognitive disabilities.

Overview

To the Reader: Alternate assessments have evolved dramatically over the past six years since they were first required by the 1997 amendments to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. This report focuses on the evolving definitions of appropriate scoring criteria for these assessments. It is targeted to readers who are familiar with the basic approaches and methods of alternate assessment, but who are working toward increased understanding of the unique challenges of defining achievement for students with significant cognitive disabilities, one of the populations for whom alternate assessments may be appropriate. For readers who are not familiar with the recent history and methods of alternate assessments, we recommend as background the Web site http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO and the specific pages on alternate assessment found on the left side menu on that site. An overview of alternate assessment and frequently asked questions can be found there, as well as links to numerous articles and resources on alternate assessment. The 2001 No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) has implications for the development of alternate assessments, and it is possible that this law will result in reinterpretations of policies and best practices for alternate assessment. This paper should be viewed as a study of current state practices and not an interpretation of the requirements of NCLB.

Over the past century, the educational community and the public have become familiar with the tools of the educational achievement test and measurement trade. Almost every adult in our society has personal experience with standardized achievement testing, for better or worse. We "know" what public school testing looks like: a group of students sits in the school cafeteria or gymnasium, nervously clutching a supply of number 2 lead pencils, well briefed on techniques to fully and completely mark the bubble sheets, waiting for instructions to turn to the first page of the test booklet. In those test booklets are test items in a variety of formats, for example, multiple-choice, true and false, short answer, or essay items.

What many educators and the public do not know is why or how those particular items–and the blend of item formats–are chosen. By the time the test booklet and bubble sheet are in the hands of the test takers, a great deal of thought and decision-making has taken place, but that work is invisible to the test taker. Typically, for tests currently required by states for the large-scale assessment of student achievement, the test is the end product of a development and field test process managed by a test company and state personnel, working collaboratively with assessment and curriculum specialists. One decision they have made is the test’s content specifications. These specifications define what knowledge and skills are tested and how students should demonstrate their ability to use the knowledge and skills. For example, in mathematics, decisions are made about how many items test basic computation skills, how many items test problem-solving abilities, and how many items test other important mathematics constructs. Decisions are made about the depth and breadth of coverage of the content, and the degree of cognitive complexity of the items. Similarly, decisions are made about how student responses are scored. For example, each item may have one correct answer, and that correct answer gets one point. Points may be deducted for incorrect answers, or scoring criteria may allow points for "partially correct" in some way. The "number correct/incorrect" on these items gives the information needed to identify which students have achieved important knowledge and skills used in school and in the future. For short answer or essay items, criteria are developed to score the open-ended student responses, reflecting the knowledge and skills that all children should know and be able to do. All in all, it takes multiple years to develop a test that meets basic standards of test quality.

Thus, once test booklets are in the hands of the students, test items reflect educator and measurement expert understanding of how to measure successful student outcomes, and this understanding ultimately is reflected in achievement scores. This understanding is assumed within the items and the way student responses are scored. Because of the years of experience test developers have had with this kind of achievement testing, these underlying assumptions are rarely discussed or debated publicly, and are invisible to all but those most closely associated with the testing process.

Some adults in our society have not had direct experience with achievement tests like those described above. Until the past decade, many students with disabilities were exempted from participation in large-scale assessments. Although exemption practices varied across the states, students with the most significant cognitive disabilities were almost always exempted. Until recently, very few educators and almost no large-scale measurement experts or test companies had direct experience in defining what successful outcomes are for this very small population of students, at least as these outcomes are defined through measurement of academic achievement. As a result, there is not a century of educator and measurement expert understanding and consensus about how to construct large-scale assessments for students with significant cognitive disabilities, or how this understanding ultimately can be reflected in academic achievement scores.

That situation is changing, however. Over the past decade, state, district, and school staff have become familiar with federal requirements that students with disabilities participate in state and district assessment systems, and that assessment accommodations and alternate assessments be provided for students who need them. The Improving America’s Schools Act of 1994 (IASA), the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act reauthorization of 1997 (IDEA), and the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) all contributed to the trend toward including students with disabilities in assessment. IDEA 1997 first identified alternate assessment as an option for students who cannot participate in general assessments even with accommodations. At the end of the 20th century many states had developed alternate assessments to meet that requirement (Thompson & Thurlow, 2001), although many were still uncertain as to how they would incorporate the results of alternate assessments into accountability formulas (Quenemoen, Rigney, & Thurlow, 2002).

NCLB raises the stakes of these accountability efforts and requires that states must specify annual objectives to measure progress of schools and districts to ensure that all groups of students reach proficiency within 12 years. Provisions included in the proposed regulations for NCLB would allow the use of alternate achievement standards for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities, provided that does not exceed 1.0 percent of all students; and that these standards are aligned with the State’s academic content standards and reflect professional judgment of the highest learning standards possible for those students. These provisions were included in the proposed NCLB regulations published in March 2003. In the context of these new accountability requirements, and despite the current uncertainty over the ultimate regulations to be applied to standards for alternate assessments, states are developing scoring criteria that reflect assumptions about what successful outcomes are for students with significant cognitive disabilities in order to ensure that achievement measures reflect these values and assumptions. It is possible that some state alternate assessments, including some described in this report may need to be modified as NCLB requirements are implemented and clarified.

Purpose of This Report

In this report, we discuss how selected states are addressing the challenge of defining successful outcomes for students with significant disabilities as reflected in state criteria for scoring alternate assessment responses or evidence. We describe how these definitions of successful outcomes have been refined over time to reflect growing understanding of the highest learning standards possible for these students. We articulate the underlying values embedded in alternate assessment scoring criteria used by these states, and identify the common ground and the differences that exist across the states as reflected by these values.

Status of Research-based Understanding

States must take several steps in the development of alternate assessment to ensure that achievement standards can be set that truly reflect what the highest learning standards possible are for this small population of students. Numerous researchers are examining the methods used in states to extend or expand the state content standards for the purpose of aligning alternate assessments to the same academic content as the general assessments (Browder, 2001; Browder, Flowers, Ahlgrim-Delzell, Karvonen, Spooner, & Algozzine, 2002; Kleinert & Kearns, 2001; Thompson, Quenemoen, Thurlow, & Ysseldyke, 2001). Others are exploring standard-setting approaches that can be used for alternate assessment in order to define what "proficient" means for accountability purposes (Olson, Mead, & Payne, 2002; Roeber, 2002; Weiner, 2002). In order for extended academic content and achievement standards to make sense for this population, additional work must be done on the criteria used to score alternate assessment responses or evidence. These criteria-setting efforts can build on early investigations that attempted to identify common understanding of what successful outcomes are for students with significant cognitive disabilities (Kleinert & Kearns, 1999; Ysseldyke & Olsen, 1997).

Following the 1997 reauthorization of IDEA, Ysseldyke and Olsen (1997) addressed assumptions that drive alternate assessments and identified four recommendations that shaped early state criteria decisions. They suggested that alternate assessments:

1. Focus on authentic skills and on assessing experiences in community/real life environments.

2. Measure integrated skills across domains.

3. Use continuous documentation methods if at all possible.

4. Include, as critical criteria, the extent to which the system provides the needed supports and adaptations and trains the student to use them.

Kleinert and Kearns (1999) surveyed national experts in the education of students with significant disabilities and found the highest ranked indicators of successful outcomes were integrated environments, functionality, age appropriateness, and choice-making. However, many respondents raised questions about the appropriateness of a focus on functional domains in an era of standards-based reform for all students, and the requirement in the 1997 reauthorization of IDEA that students should have access to, participate in, and make progress in the general curriculum. A discussion ensued among researchers and practitioners about the relationship of general academic content areas and functional outcomes. Thompson and Thurlow (2001) found that by the turn of the century, a shift to standards-based alternate assessment measurement approaches and a focus on the general curriculum was adopted by most states, reinforced by regulations and guidance on federal assessment policy.

Yet, the Thompson and Thurlow 2001 survey of state assessment practices found a continued range of alternate assessment approaches (see Table 1 for a summary description of the alternate assessment approaches we address in this report), and more importantly, no clear consensus on the criteria being used to score alternate assessment evidence. The survey also illustrated the complexities of definitions, both for the approaches themselves, as well as for the criteria used for scoring. These complexities can confuse any discussion attempting to compare and contrast varying approaches in a categorical way. In the interests of sorting out these complexities, the reader may wish to carefully review the discussion of the overlap among approaches below, and refer to this later as we sort through variations in our sample states. Table 1 (Definitions of Alternate Assessment Approaches Discussed in this Paper) and Table 2 (Common Scoring Criteria Terminology) are provided as a quick glance summary to refer to later in this report, as well as to provide a summary of the discussions below.

Alternate Assessment Approaches: Not Mutually Exclusive Categories

In general, the alternate assessment approaches defined in Table 1 go from a basic methodology of student-by-student individually structured tasks (portfolio assessment) to highly structured common items or tasks completed by every student (traditional tests) as you read down the table. These approaches are not mutually exclusive categories, and as state practices are examined, it is clear that a great deal of overlap in methods occurs.

Portfolio Overlap with IEP Linked Body of Evidence

The "portfolio" approach typically requires the gathering of extensive samples of actual student work or other documentation of student achievement. Very often, this work is in response to teacher-developed tasks with teacher-defined linkage to content standards, thus the evidence varies dramatically from one student to the next. It is the standardized application of scoring criteria to the varied evidence that results in comparability across students. "IEP linked body of evidence" approaches as defined here also may require extensive sampling of work, have similar scoring criteria, and apply them in similar ways to the portfolio approach. However, in this report, the states using a portfolio approach require extensive student products; the state that uses an IEP linked body of evidence has more focused evidence requirements, related specifically to the skills and knowledge defined in the student’s IEP, and the documentation of progress in the IEP process. In general, the distinguishing characteristics between "portfolio" approaches versus "body of evidence" approaches tend to be, for the purpose of this report:

(1) the amount of evidence required is more for portfolio, less for body of evidence;

(2) the degree of state provided definition of what specific content is measured is less with portfolios, and there is more state provided definition of specific content for a body of evidence; and

(3) the degree of IEP linkage is less for portfolio and more for a body of evidence.

(A complicating variable is how advanced a state is in implementing standards-based IEP planning, thus the IEP linkage to alternate assessments may be "pushing the envelope" of standards-based reform for students with disabilities. That discussion is beyond the purpose of this report, but will be increasingly important as alternate assessment evolves.)

Table 1. Definitions of

Alternate Assessment Approaches Discussed in this Paper

Portfolio: A

collection of student work gathered to demonstrate student performance on

specific skills and knowledge, generally linked to state content standards.

Portfolio contents are individualized, and may include wide ranging samples of

student learning, including but not limited to actual student work, observations

recorded by multiple persons on multiple occasions, test results, record

reviews, or even video or audio records of student performance. The portfolio

contents are scored according to predefined scoring criteria, usually through

application of a scoring rubric to the varying samples of student work.

IEP Linked

Body of Evidence: Similar to a portfolio approach, this is a

collection of student work demonstrating student achievement on standards-based

IEP goals and objectives measured against predetermined scoring criteria. This

approach is similar to portfolio assessment, but may contain more focused or

fewer pieces of evidence given there is generally additional IEP documentation

to support scoring processes. This evidence may meet dual purposes of

documentation of IEP progress and the purpose of assessment.

Performance Assessment: Direct measures of student skills or knowledge, usually in a one-on-one assessment. These can be highly structured, requiring a teacher or test administrator to give students specific items or tasks similar to pencil/paper traditional tests, or it can be a more flexible item or task that can be adjusted based on student needs. For example, the teacher and the student may work through an assessment that uses manipulatives, and the teacher observes whether the student is able to perform the assigned tasks. Generally the performance assessments used with students with significant cognitive disabilities are scored on the level of independence the student requires to respond and on the student’s ability to generalize the skills, and not simply on accuracy of response. Thus, a scoring rubric is generally used to score responses similar to portfolio or body of evidence scoring.

Checklist: Lists of skills, reviewed by persons familiar with a student who observe or recall whether students are able to perform the skills and to what level. Scores reported are usually the number of skills that the student is able to successfully perform, and settings and purposes where the skill was observed.

Traditional (pencil/paper or computer) test: Traditionally constructed items

requiring student responses, typically with a correct and incorrect

forced-choice answer format. These can be completed independently by groups of

students with teacher supervision, or they can be administered in one-on-one

assessments with teacher recording of answers.

Adapted from Roeber,

2002.

Body of Evidence Overlap with Performance Assessment

The "body of evidence" tendency toward more focused and specific evidence in turn reflects a similarity with the least structured specific "performance assessment" approaches in other states. That is, some performance assessment approaches define the skills and knowledge that must be assessed for each student, but they still allow the test administrator to structure a task that the student will perform to demonstrate the skills and knowledge. The most structured body of evidence approaches tend to be very similar to the least structured performance assessments. In other words, a state may require in a performance assessment OR a body of evidence that a student demonstrate his or her reading process skills by identifying facts, events, or people involved in a story. How the student demonstrates those skills will vary, and the task could involve, for example:

• requiring that a student use a switch to provide different sound effects corresponding to characters in a story, whether read by the student or teacher;

• having a student look at pictures to identify favorite and least favorite parts of a story that was read aloud; or

• a student reading a simple story and then making predictions of what will happen next using clues identified in the text.

As a further source of individualized tailoring in either a highly structured body of evidence or a loosely structured performance assessment, each of these tasks could allow for varying levels of teacher prompting, and thus scoring criteria could include the criterion of the level of prompting/degree of independence. Where the approaches differ is that a body of evidence approach generally requires submission of the student evidence for scoring; a performance assessment approach typically involves the test administrator or teacher scoring student work as it occurs.

Other states that define their approach as a performance assessment provide a high degree of structure and specifically define the task (e.g., having a student look at pictures to identify favorite and least favorite parts of a story that was read aloud, with provided story cards and materials). Yet they typically allow variation in the degree of prompting (ranging from physical prompts to fully independent responses), or in the methods of student responses (from use of picture cards vs. verbal response for example). Even states that use common performance assessment tasks for their required alternate assessment for students with significant disabilities tend to use multiple scoring criteria more similar to portfolio or body of evidence approaches, as compared to simple recording of correct or incorrect responses used in checklist or traditional test formats.

Performance Assessments Overlap with Checklist and with Traditional Test Formats

Most "checklist" approaches ask the reviewer to record whether a student has demonstrated the skill or knowledge. These may include a judgment on degree of independence or generalization as well as accuracy of skill performance, but the judgments may simply reflect accuracy. The difference between checklists and performance assessment approaches where the test administrator scores the performance is that the checklist approach relies on recall and not on actual on-demand student performance. By contrast, "traditional test" formats require the on-demand performance of skills and knowledge, on a specified item, with built in connection to content standards and with accuracy (or "right/wrong") as the primary criterion. The test administrator records student performance as right or wrong, and no further scoring is necessary. This approach is the most similar to the testing approaches most adults have experienced described in the opening section of this report.

The Complexities of Criteria Definitions Across the States

As shown in the descriptions above, there is a great deal of overlap across the alternate assessment approaches, and they tend to represent a continuum of approaches as opposed to discrete categories. Regardless of what approach a state has chosen, or what they have called it, states have begun to revisit the basic assumptions and values underlying their approach to alternate assessment. Central to this effort is the challenge of clarifying what the criteria are on which evidence is judged. These criteria should reflect how state stakeholders define successful outcomes for students with significant cognitive disabilities. For example, a description of a successful outcome for these students may include the ability to do particular skills, with the highest degree of independence and self-choice possible, in a variety of settings or for different purposes, with an ability to get along with others and maintain relationships. Scoring criteria typically are constructed to be sensitive to measuring learning toward some or all of these desired outcomes.

An in-depth study that compares and contrasts approaches across a variety of states and people holding a variety of perspectives naturally runs into terminology challenges; therefore, we define several terms that we use throughout the report. In Table 2 we provide common scoring criteria terminology. The clarification of terms used in describing scoring criteria is even more complex than the clarification of the terms used to describe the alternate assessment approaches, if that is possible.

A critical set of definitions involves the

distinctions among student criteria, system criteria, and combination student

and system criteria.

Scoring Rubrics: Commonly used in scoring alternate assessment evidence or responses, scoring rubrics list the criteria that are desired in student work, along with definitions of quality expectations, generally along a 3-5 point scale. Scoring Criteria: These are specific definitions of what a score means and how specific student responses are to be evaluated. Generally based on stakeholder and research derived knowledge of what is considered best practice in teaching and learning for these students, states identify scoring criteria to encourage these best practices. These criteria can be articulated in scoring processes, or built into test specifications. Criteria for alternate assessment typically fall into one of three categories: student criteria, system criteria, and a student/system blend.

|

Adapted from Roeber, 2001

Student Criteria vs. System Criteria vs. Combination Criteria

Scoring criteria typically are developed by stakeholders in each state based on professional and research-derived understanding of desired and valued outcomes for this population of students. These can be a direct measure of student achievement (student criteria); they may reflect necessary system conditions essential for student success (system criteria); or they can be a combination of student achievement seen within the context of system provided supports (combination). The distinctions among student, system, and combination criteria are important to this study; the reader may wish to continue to refer to Table 2 for clarification as we examine criteria in each of the sample states.

Scoring Process

After defining the criteria, the scoring process is designed to reflect and capture the identified outcomes as evidenced in a sample of student work or in student responses to test items. For example, a state may choose to score student work using the two criteria they have identified as central to successful outcomes for students with significant cognitive disabilities: demonstration of specific knowledge or skills, and generalization of knowledge and skills to more than one setting or for more than one purpose. They can then decide to apply the criteria – to actually score the evidence – choosing from several scoring processes. For example, a state could apply the skill and generalization criteria through one of these processes:

1. A process that requires that student work be submitted to scoring centers, where evidence is scored by trained double blind scorers and a third tie-breaker scorer.

2. Scoring of student performance by trained test administrators observing as the student performs the skill or responds to the performance task in more than one setting or for more than one purpose.

3. A two-step process where the skill level is determined by "number correct" on a pencil/paper test, accompanied by a checklist form completed by teacher, parent, and related service provider reflecting their judgment of degree of skill generalization.

Thus, defining scoring criteria and defining the scoring process are different, yet interdependent. Setting scoring criteria has more importance in defining and detecting learning toward successful outcomes than does the scoring process; you can change scoring processes easily as you understand how processes can be improved (e.g., changing from one scorer to two scorers). Scoring criteria generally change only after serious discussion and open debate about the assumptions and values underlying each criterion.

The Relationship Between Assessment Approach and Scoring Criteria

The assumptions and values underlying scoring criteria can remain the same across alternate assessment approaches. For example, assumptions and values for scoring criteria can be the same for a body of evidence or for a performance assessment or for a pencil and paper assessment, as assumed in the example above. In traditional large-scale assessments, which generally use pencil and paper forced-choice formats, scoring criteria often are embedded in the test development processes and are not articulated in the scoring process. That is, criteria such as alignment to content standards, degree of difficulty, and appropriateness for grade level, are addressed in the test’s item development, item specifications, form development, and in field testing. For performance assessments, and sometimes for the constructed response items in traditional tests, scoring criteria generally are articulated, often in the form of rubrics. Scoring rubrics are the most common method of applying scoring criteria to portfolios and bodies of evidence.

In this study, we compare and contrast the assumptions and values embedded in scoring criteria used in five states for their alternate assessments. Given the wide range of approaches included in the states we studied, we attempted also to identify the "assumed" criteria underlying more traditional test formats, as well as to identify similar kinds of assumptions underlying more performance based approaches.

Scoring Criteria vs. Achievement Level Descriptors

One final distinction should be made between the scoring criteria that are the focus of this report and another common term used in large-scale assessment, the term "achievement level descriptors." Achievement level descriptors are generally the terms used to communicate how a state has defined "proficiency" based on test results. In the scoring process, scoring criteria are applied to responses or evidence to produce a score. This score is not in itself directly translated into an achievement level. A standard-setting process must be defined to identify what scores mean. Usually this involves identifying "cut scores" that separate achievement levels. The first cut scores identified are those based on an understanding of proficient student work. Different cuts determine gradations of quality, and result in defining a range of scores reflecting varying success. It is through this standard setting process that a state defines what scores represent "proficiency." The scoring criteria, of course, are related to the achievement levels and descriptors, but they are not the same. In this study we specifically focus on the way states have defined and are refining their scoring criteria.

Methods

Selecting States

In order to select a small number of states to study, we went through several steps. Our goal was to select states that represented different approaches and scoring criteria. Given the definitional overlaps we have described in the preceding sections, we found that grouping states into categories was not a simple process. First, we examined the results of a 2001 survey of state directors of special education that included several questions about alternate assessments (Thompson & Thurlow, 2001). All states were sorted by their responses to questions about:

a. Alternate assessment approach

b. Scoring criteria (called "performance measures" in that survey)

We identified patterns of responses on these two items, and identified "clusters" of responses to each of the two questions. From these clusters, we selected a small number of states that represented variations in the type of approach used for alternate assessment and variations in the criteria used to score alternate assessment responses or evidence.

The distribution in variations in approach identified in the 2001 survey (Thompson & Thurlow, 2001) is shown in Table 3. Because nearly half of the states reported using a portfolio or body of evidence approach (as defined in the 2001 survey these two approaches were grouped), we decided to select two of these states for the study, but ones that differed on scoring criteria. Then we planned to select one each from the other categories that had fewer states. However, we realized on closer examination that some states that had reported in portfolio/body of evidence category could also be considered as part of the IEP approaches, if the IEP linkage defined the body of evidence. That realization required a revisiting the original clusters, and regrouping based on information we had available in our files from Web sites and from the states. Upon review, we realized that the approach reported by states on the 2001 survey was not always the most accurate label, and we adjusted our clusters of state approaches to match what we found in state descriptions provided in public forums, not simply what was reported on the survey.

| Body of evidence/ portfolioa | 24 states |

| Checklist | 9 states |

| IEP team determines strategy | 4 states |

| IEP analysisb | 3 states |

| Combination of strategies | 4 states |

| Specific performance assessment | 4 states |

| No decision | 2 states |

a

Defined by the submission of student work or other documentation.

Table 4. Student and System Scoring Criteria Across States

| Student Scoring Criteria | |

Skill/competence |

40 states |

Independence |

32 states |

Progress |

24 states |

Ability to generalize |

18 states |

Other |

7 states |

System Scoring Criteria |

|

Variety of settings |

21 states |

Staff support |

20 states |

Appropriateness (e.g., age, challenge) |

20 states |

Gen. ed. participation |

12 states |

Parent satisfaction |

9 states |

No system measures |

8 states |

Again, several factors contributed to reorganizing the states we considered for our sample. From correspondence with states as part of NCEO’s technical assistance activities, we were aware that several states were in the process of changing their assessment approach or their scoring criteria. For example, several states that had reported IEP based approaches in 2001 have since indicated to us that they are in the process of developing a different approach. In addition, several other states had indicated to us that they anticipated changes in their scoring criteria after their first year of implementation and were undecided as to how they would proceed. In order to ensure that we would be analyzing thoughtfully conceived and fairly stable state approaches, we used a purposive sampling technique informed by two indicators. One indicator of stability was that the state had presented its approach and scoring criteria in public forums such as the annual alternate assessment pre-sessions to the CCSSO large-scale conferences, or at the Assessing Special Education Students (ASES) State Collaborative on Assessment and Student Standards (SCASS) meetings. The second indicator was that the state had at least two years of statewide experience with the alternate assessment in the current form, with no substantial changes.

Based on review of materials provided by the states at these public forums, we found that within the portfolio group the approaches to scoring criteria varied depending in part on what test company had supported development of the assessment. For that reason, we decided to select the two states representing portfolio approaches to ensure that two different test company approaches would be represented. We also looked for states that generally conformed to the current understanding of quality assessment approaches as reflected in the NCEO Principles and Characteristics of Inclusive Assessment and Accountability Systems (Thurlow, Quenemoen, Thompson, & Lehr, 2001).

This purposive and somewhat subjective sampling process resulted in a much smaller group of states from which to choose. From this group, we chose two portfolio approach states that differed in scoring criteria (and testing company), and one state each representing performance assessment, combination and checklist approaches, and an IEP approach, which represented the IEP linked body of evidence subcluster. The final decision to include particular states was made in part to ensure that the widest range of criteria definitions was represented, and that the states chosen represented the widest possible range of test companies/developers, while still ensuring the basic quality of the approach. We requested and received agreement from the five states selected to participate in the study. The states were Arkansas (portfolio assessment), Kentucky (portfolio assessment), Louisiana (performance assessment), Oregon (combination/checklist), and Vermont (IEP linked body of evidence).

Data Collection Process

The study included both a document review and interview process. The purpose of the document review was to describe each state’s approach to alternate assessment, and to identify and report the scoring criteria used to score assessment responses or evidence in each state. The specific terms used by states for this process varied (e.g., scoring rubrics, scoring criteria, scoring domains, scoring rules, or simply number correct for pencil/paper tests). The focus of the interviews was on how each state developed its scoring criteria, definitions, and assumptions. We also asked states how and why these criteria have changed over time, and finally, how states see the criteria being used to improve the education of students with significant disabilities. The interview guide is included in Appendix A.

After an NCEO staff member conducted the document review, written summaries were sent to each state contact person for review, correction, and verification. The same staff member conducted interviews by phone with all of the state contacts. A second staff member reviewed interview recordings and supporting documentation, and developed written anecdotal case studies. The final draft materials were subject to review and comment by the states for accuracy and additional insight.

A final step was taken to compare and contrast the documented and anecdotal understanding of the assumptions each state reflected in its scoring criteria. Through a "side by side" view of the states’ scoring criteria (obtained from both written documentation and phone interviews), we proposed common themes that represent the underlying values embedded in each state’s scoring criteria and processes. We also attempted to delineate the common ground that exists across the states.

The approaches and criteria reported in the 2001 state survey for the five states included in this study are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Approaches and Criteria Reported on NCEO's 2001 Survey by the Five Selected StatesState

|

Approach |

Student Scoring Criteria |

System Scoring Criteria reported on 2001 Survey |

|

Portfolio |

a, c |

b, c |

Portfolio |

a, b, c, d |

a, b, c, d, e |

|

Performance Assessment |

a,

c, d |

None |

|

Combination: Checklist,

performance assessment, pencil/paper test |

e

(number correct on pencil/paper exam) |

b, c (on performance assessment) |

|

Evidence/IEP linkage |

a, b |

Other (not described) |

Student Scoring Criteria: a=skill/competence level; b=degree of progress; c=level of independence; d=ability to generalize; e=other.

System Scoring Criteria: a=staff support; b=variety

of settings; c=appropriateness (age appropriate,

challenging, authentic); d=parent

satisfaction; e=participation in general education. None = No system criteria.

Based on

the 2001 survey of state directors of special education, conducted by the

After document reviews and interviews, we found the actual scoring criteria used by each state varied somewhat from the categories provided in the 2001 survey. We present here the criteria as presented in state documentation, followed by a more detailed description of each state’s articulated and assumed scoring criteria based on documentation and interviews.

Since we are focusing on the complexities of scoring criteria in these descriptions, we provide very few details on the general methods of the state’s overall approach. This assumes that the reader has a basic understanding of varied alternate assessment approaches, including portfolios, bodies of evidence, performance assessments, and checklists or traditional test formats. We recommend reviewing the alternate assessment pages of the NCEO Web site at http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO or visiting each of our sample state’s Web sites for more information on the basic approaches. We have made a judgment and have confirmed through our document review and interviews that these five states share three basic quality indicators. First, each state developed its alternate assessment through an open process involving varied state stakeholders, including teachers, parents, researchers, and technical advisors. Thus, each reflects professional and research based understanding of the best possible outcomes for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Second, each of these states continues to work to understand and document the technical adequacy of its approach, including documenting and improving the reliability and validity of their approach. Third, each of these states can articulate a coherent alignment of its basic assumptions underlying teaching and learning for these students, and the approach and criteria it has chosen to assess that learning. Although the states differ from one another, each reflects a thoughtful approach. This does not mean that these sample states have "perfect" or even "approvable" alternate assessments, or that they will continue far into the future with the methods described here. What it does mean is that we have confidence in the internal consistency and integrity of these state approaches given current understanding of best practices in alternate assessment for students with significant disabilities.

Scoring Criteria in Arkansas

Arkansas uses a portfolio assessment approach, and has a scoring rubric, domain definitions, and scoring weighting processes to define its scoring criteria. Table 6 shows Arkansas’s four scoring domains and the criteria used to assign a score from 1 to 4 on each domain to each entry in a portfolio. Only the first three domains are scored for each entry; the last (settings) is scored for the entire content area. The domains are weighted differently.

Table 6.

DOMAIN* see definitions below

|

Score 1 |

Score 2 |

Score 3 |

Score 4 |

PERFORMANCE |

Student

does not perform the task with any evidence of skill |

Student

attempts the task, but there is only minimal evidence of skill |

Student

performs the task with reasonable skill |

Student

performs the task with mastery as demonstrated in multiple settings or on

multiple occasions |

APPROPRIATENESS |

Task does

not meet any of these criteria: age-appropriate, challenging or authentic |

Task

meets only 1 of these criteria: age-appropriate, challenging or authentic |

Task

meets 2 of these criteria: age-appropriate, challenging or authentic |

Task

meets all 3 of these criteria: age-appropriate, challenging and authentic |

LEVEL OF

ASSISTANCE |

Following

the introduction of the lesson or activity, student performs only with

maximum physical assistance (such as hand-over-hand support) |

Following

the introduction of the lesson or activity, student performs with direct

verbal prompting, modeling, gesturing or some physical support |

Following

the introduction of the lesson or activity, student performs in response to

teacher-planned instructional/ social supports

(e.g., peers, technology, materials supports) |

Following

the introduction of the lesson or activity, student performs independently

OR student initiates the activity with the use of natural environmental or

social supports |

SETTINGS |

Student

performs all tasks in 1 physical setting (e.g., classroom) |

Student

performs tasks in 2 different settings |

Student

performs tasks in 3 different settings |

Student

performs tasks in 4 or more different settings |

Table 7 shows how the number of entries, domain weights, and points possible per entry produce the total points possible for each portfolio. Note that two scorers score each of the first three domains, and the cumulative score is used to determine the total points. It also shows the percentage of a score that is due to each domain. Again, the setting score is given collectively across all math entries and all English Language Arts entries, and not to each entry.

Table 7. Arkansas Weighting of Mathematics and English Language Arts Entries by Domain

Mathematics Entries

5 strands with 3 entries each

DOMAIN |

Scorers |

No. Entries |

Domain Weight |

Points Possible |

TOTAL POINTS |

Percent |

Performance |

2 |

15 |

4 |

4 |

480 |

53 1/3 |

Appropriateness |

2 |

15 |

2 |

4 |

240 |

26 2/3 |

Level of Assistance |

2 |

15 |

1 |

4 |

120 |

13 1/3 |

Settings |

1 |

15 |

1 |

4 |

60 |

6 2/3 |

900 |

100% |

|||||

English Language Arts Entries

3 strands with 3 entries each

DOMAIN |

Scorers |

No. Entries |

Domain Weight |

Points Possible |

TOTAL POINTS |

Percent |

Performance |

2 |

9 |

4 |

4 |

288 |

53 1/3 |

Appropriateness |

2 |

9 |

2 |

4 |

144 |

26 2/3 |

Level of Assistance |

2 |

9 |

1 |

4 |

72 |

13 1/3 |

Settings |

1 |

9 |

1 |

4 |

36 |

6 2/3 |

540 |

100% |

|||||

Scoring Criteria in Kentucky

Kentucky uses a portfolio assessment approach. Table 8 shows the six scoring dimensions and the scoring criteria used to assign a score of novice, apprentice, proficient, or distinguished to each dimension. When all dimensions have been scored, a holistic proficiency level is assigned to the entire portfolio.

Table 8.

NOVICE |

APPRENTICE |

PROFICIENT |

DISTINGUISHED |

|

STANDARDS |

Portfolio

shows little or no linkage to academic expectations |

Portfolio

shows some linkage to academic expectations |

Portfolio

shows linkage to most academic expectations |

Portfolio

shows linkage to all or nearly all academic expectations |

PERFORMANCE |

Student

portfolio participation is passive, no clear evidence of performance of

target IEP goals, products are not age-appropriate |

Student

performs target IEP goals meaningful to current and future environments,

products are age-appropriate |

Student

work shows progress on target IEP goals meaningful to current and future

environments in most entries, products are age-appropriate |

Student

work shows progress on target IEP goals meaningful to current and future

environments in all entries, products are age-appropriate |

SETTINGS |

Student

participates in limited number of settings |

Student

performs target IEP goals in a variety of integrated settings |

Student

performs target IEP goals in a wide variety of integrated settings within

and across most entries |

Student

performance occurs in an extensive variety of integrated settings within and

across all entries |

SUPPORT |

No clear

evidence of peer supports or needed A/M/AT |

Support

is limited to peer tutoring, limited use of A/M/AT |

Support

is natural, appropriate use of A/M/AT |

Support

is natural, use of A/M/AT shows progress toward independence |

SOCIAL |

Student

has appropriate but limited social interactions |

Student

has frequent, appropriate social interactions with a diverse range of peers |

Student

has diverse, sustained, appropriate social interactions that are reciprocal

within the context of established social contacts |

Student

has sustained social relationships and is clearly a member of a social

network of peers who choose to spend time together |

SELF- |

Student

makes limited choices in portfolio products; P/M/E of own performance is

limited |

Student

makes choices that have minimal impact on student learning in a variety of

portfolio products; P/M/E of own performance is inconsistent |

Student consistently makes choices with significant impact

on student learning; P/M/E of own performance is consistent |

Student

makes choices with significant impact on student learning within and across

all entries; P/M/E of own performance is clearly evident; E is used to

improve performance and/or set goals |

A/M/AT = adaptation, modification and/or assistive technology

P/M/E = planning, monitoring, evaluating

Because Kentucky has had an alternate assessment in place several years longer than any other state, it has a system that is the result of many years of continuous improvement. In the process of implementing the Kentucky Alternate Portfolio across almost a decade, Kentucky has learned important lessons about its scoring criteria, and has revised them as a result. For example, in the early years of implementation, self-determination was not a separate dimension. First, it was part of performance; then it was part of context. Because self-determination was moved out of "performance," and then out of "context" to its own dimension, scores could not be compared across years. For the past three years no changes have been made in the criteria. Table 9 describes the lengthy process of continuous improvement that Kentucky has experienced.

Table 9. A Decade of Continuous Improvement in Kentucky

In 1990

A small group consisting of state department

personnel, university personnel, teachers, parents, and local education

administrators met to begin looking at the best ways to assess students with the

most significant disabilities. They sent out surveys across the state and

acquired a lot of information. They decided that a portfolio approach would be a

good format for compiling assessment information. Once the alternate assessment

was developed, this group continued to meet every summer to make revisions and

clarifications based upon current literature and research findings in special

education, and to design better ways to train teachers.

In order to use the portfolio for program

accountability, the group reviewed research literature for components of best

practice, research-based instruction. They listed five areas found critical to

the education of students with the most significant disabilities. These

included: settings, support, social relationships, performance, and contexts.

When IDEA was passed in 1997,

The criteria and scoring rubric did not change at that

point. It still contained the same five dimensions. However, some recombining

took place. For example, in the performance area there were a lot of concepts

that seemed like self-determination, so they were moved to the context area.

Later, the context area was changed to self-determination.

Linkage to standards was addressed

in the performance area, but in 1998 the stakeholder group decided it was not

confident in the way adherence to standards was scored. The portfolio required

standards to be addressed, and scorers looked for them, but addressing standards

was not really scored. There was a connection because of the content area and

focus on the general curriculum. As

Scoring Criteria in Louisiana

The complete Louisiana assessment program is called Louisiana Educational Assessment Program, or LEAP. The alternate assessment is titled LEAP Alternate Assessment (LAA). The LAA is a performance-based student assessment that evaluates student knowledge and skills on twenty target indicators for state selected Louisiana Content Standards. It is an "on-demand" assessment. The test administrator (teacher or other school staff trained in LAA) organizes activities so that the student can show what he or she knows and can do (target indicators), and then uses a rubric to score the student’s performance of state specified standards-based skills. Skills for each target indicator are identified on three levels of difficulty, called Participation Levels. The levels are called Introductory, Fundamental, and Comprehensive. The participation level for each student is chosen by the test administrator, with IEP team input, based on appropriate yet high expectations for each student. Participation levels are defined in Table 10.

Table 10. Participation Levels in Louisiana

Introductory: Skills that require basic processing of information to address real-world situations that are related to the content standards, regardless of the age or grade level of the student (e.g., indicates choice when presented with two items). Fundamental: Skills that require simple decision making to address real-world situations that are related to the content standard, regardless of the age or grade level of the student. (e.g., expresses a preference to the question "what do you want?"). Comprehensive: Skills that require higher-order thinking and complex information-processing skills that are related to the content standards, regardless of the age or grade level of the student (e.g., communicates detailed information about preferences, such as, describes activity with information about who, what, when, where, why. . .). |

Table 11 shows the Louisiana alternate assessment scoring rubric, which includes two criteria, level of independence and evidence of generalizability to multiple purposes and settings. That is, the rubric measures progression from dependence to independence, and from particular skill to generalized skill.

Table 11. Louisiana Scoring Criteria

Given student performance of the

standards-based skill at the appropriate performance level,

0: No performance (at introductory level only).

1: Tolerates engagement or attempts engagement.

2: Performs skill in response to a prompt.

3: Performs skill independently without a prompt.

4: Performs skill independently without prompts for

different purposes OR in multiple settings.

5: Performs skill independently without prompts for

different purposes AND in multiple settings.

Scoring Criteria in Oregon

Oregon uses four individually administered performance assessments: one of these is the Extended Career and Life Role Assessment System (CLRAS), the other three are Extended Reading, Extended Mathematics, and Extended Writing, three separate measures aligned to the Oregon Standards in reading/literature, mathematics, and writing. The Extended CLRAS assesses related skills in the context of "real" life routines and is administered individually as a performance assessment by a qualified assessor, usually the student’s teacher. The selection of routines is informed by the results of a teacher-completed checklist while related skills are selected from the students IEP. The Extended CLRAS is aligned to the Career Related Learning Standards adopted by Oregon’s State Board for all students. Extended Reading, Extended Mathematics, and Extended Writing employ curriculum based measures of emerging academics and are aligned to the general Benchmark 1 standards in the same subjects. Students may take one or more of these extended assessments; some students take only the Extended CLRAS. For extended measures in reading, mathematics, and writing, the scores are derived from the number of correct or partially correct items. For the Extended CLRAS, qualified assessors evaluate performance on related skills in the context of core steps of daily life routines according to a rating scale. There are some items, like symbol recognition, at the very lowest end of the extended assessments in reading, mathematics, and writing that seem compatible with Extended CLRAS, and there are some items at the upper end that are sensitive to growth similar to items on the general assessment.

Scoring criteria for the extended assessments in reading, mathematics, and writing are shown in Table 12. Oregon hopes to use results of the alternate assessment for predicting performance on regular assessments whenever that is appropriate. For the general assessment there are four benchmark standards: Benchmark 1, 2, and 3, and the CIM – the Certificate of Initial Mastery benchmark. The state is considering the use of a benchmark "P" for predictive or preliminary that would apply to the scores on the extended academic assessments. A "P" would indicate that sometime in the future the student may be moving to Benchmark 1, and thus into the general assessment.

Table 12. Scoring Criteria for Oregon’s Extended Reading, Extended Mathematics, and Extended Writing Assessments

Accuracy is the articulated criterion. Each individual task item is scored correct or partially correct. The scores relate to level of accuracy on letters, numbers, words, reading rate, reading accuracy, reading and listening comprehension, number concepts, computation, dictation, plus writing words, sentences, and a story.

are embedded into the items themselves, just as they are for the general assessment. Given the growth model, student progress is also an assumed criterion in the Extended Reading, Extended Mathematics, and Extended Writing assessments. |

Some students take only the individually administered Extended CLRAS, a performance assessment and checklist; others take the Extended CLRAS along with one or more extended assessments in reading, mathematics, and writing. A six-point scale is used to score student performance of defined "routines" (routines are selected by the qualified assessor and informed by the checklist results) on the Extended CLRAS (see Table 13). Scores of 1 to 4 reflect increasing levels of independence on the individually selected routines and skills. Two of the scores indicate the task was not done, either because it was not applicable (N) or the student could not do it at all (0). Although the scale does not include a criterion related to generalization, state staff reported in the interviews that generalization across settings is imbedded into the design of the Extended CLRAS. It is instructionally based, so students have continued instruction and are measured in areas where they are acquiring independence. As students become more independent and master environments, additional routines are selected. A high value is given to having students learn and demonstrate their related skills in natural environments, and this is reflected in scoring. Scoring of the Extended CLRAS puts emphasis on prompt fading, but if the student does seven routines, and "social greetings" is one of the related skills performed, then there are seven appropriate environments defined in which to exhibit that related skill. Thus, generalization is embedded in the scoring process.

Table 13. Scoring Criteria for Oregon’s Extended CLRAS

4 = completes independently

3 = completes with visual, verbal or gesture prompting

2 = completes with partial physical prompting

(requires at least one physical prompt, but not continuous physical prompts)

1 = completes with full physical prompting (requires

continuous physical prompts)

0 = does not complete even with physical prompting

N = not applicable (due to student’s medical needs,

the school environment does not provide an opportunity to perform, or the IEP

team deems the routine/activity inappropriate for the student)

Scoring Criteria in Vermont

There are three alternate assessments in Vermont: an adapted form of the general assessment, a modified form of the general assessment, and a "lifeskills" alternate assessment for students with significant cognitive disabilities. The modified and adapted assessments are for students who are able to take the general assessment with specific adaptations or modifications. The students who participate in adapted assessments are generally students with sensory impairments who cannot take the regular test because of lack of Braille versions or other lack of appropriate accommodations. The adapted assessment measures the same standards, at the same proficiency levels, as the regular assessment. Modified assessments result in changes to the construct being measured, generally for students who are performing below grade level. These options do not apply to students with significant cognitive disabilities; thus only the lifeskills assessment is described in this study.

Vermont’s lifeskills assessment consists of a complex interplay of IEP goals and objectives, Vermont standards, and a body of evidence. The description of the lifeskills alternate assessment reflects this interplay:

• it is based on a portfolio of individually-designed assessments, typically those used to measure IEP progress (body of evidence)

• it measures progress toward mastery of key learning outcomes

• learning outcomes are validated through research

• it is referenced to Vermont standards

• it parallels regular assessment through grades when assessment occurs, assessment content, scoring criteria

• it measures student performance and program components

Four criteria are applied in the scoring process for the lifeskills assessment. These are shown in Table 14. As indicated in the table, movement from one criterion to the next is dependent on meeting the first criterion.

Table 14. Vermont Scoring Criteria

Outcome or Related

Standard is Referenced in the IEP: The learning outcome can be quoted directly, paraphrased, or

can be referenced to the corresponding Vermont Standards listed in the rubric.

The outcome might be embedded in a larger goal or outcome. Quality

gradations:

0 or 1. If 1, can go to next criterion.

Learning Outcome or

Related Standard is Assessed in the IEP: This is evidenced if there are IEP goals, objectives or

references to progress measures that will show whether the student is making

progress toward mastering the designated learning outcomes. Quality

gradations: 0 or 2. If 2, can go to next criterion.

Progress Toward Mastery of Learning Outcome or Related Standard:

Progress is defined as development, improvement, or positive changes in the

student’s performance in relation to designated learning outcomes, including

incremental skill development, fading of supports, or generalization to more

natural settings. In addition, progress must be measured at least two points in

time (i.e., pre-test/post-test), but preferably at multiple times across the 9 -

12 month period. Amount or rate of progress is not measured, only that it has or

has not occurred. This can occur with incremental achievement of skills, with

incremental fading of supports, or through generalization of skills to less

restrictive environments. Quality gradations: 0 or 2. If 2, can go to

next criterion.

Mastery:

For the purpose of scoring the Lifeskills Portfolio, mastery is defined as the

ability to perform a targeted skill or ability independently, or using natural

supports and assistive technology that permit independence. If the student needs

a parent, teacher, or instructional assistant to perform the skill, independence

has not been demonstrated and a “0” should be given.

For some students with degenerative disabilities or

health impairments, they may demonstrate progress by “standing still” or

regressing as slowly as possible. In these rare cases, maintenance related to

quality of life indicators, may be the most appropriate progress measure. This

kind of “progress” might be documented through logs, team notes, or other

anecdotal records. Quality gradations: 0 or 1.

Lessons Learned about Scoring Criteria in the Five States

Early in our review of documents and in state interviews, as we developed an understanding of each state approach, we began to see overlaps, new differences, and shades of meaning underlying the scoring criteria in different states.

Articulated, Embedded, or Assumed Criteria

Some states, for example, score on the quality of a teacher-designed linkage to state academic content standards, while other states embed this linkage into the assessment instruments themselves, so students are directly assessed on their performance on standards-based items. One state scores directly on the IEP linkages, but all four of the other states address IEP linkages through training or in the design of the assessment. We were able to ferret out this variation through the interview process and through written materials sent to us by the five states. This analysis is described here, accompanied by a side-by-side analysis in which we include the actual criteria scored, but also note when a criterion is assumed within the design of the system, although not articulated.

Overlapping Purpose

The distinction between student and system criteria highlighted in the past (e.g., Thompson & Thurlow, 2001) was not as clear in our analysis; we saw overlap in the purpose of the criteria. For example, how do the student measures of generalization and the system measures of multiple settings differ? Some states look for evidence that the student can perform a task in multiple settings as an indicator of generalization of the skill. Other states look for multiple settings offered to students as they are instructed as a measure of system support for high program quality. Is not the purpose of requiring that the system provide multiple settings reflected in the increased generalization of skills shown by the students within the settings? Yet these approaches do differ. With the system approach, the multiple settings are rewarded even if the student has not shown mastery or progress on skills in all areas. In states with the system approach, it seems to be assumed that for these students, whose progress is slow and sometimes hard to document, the offering of the settings is in itself a value to reinforce, regardless of student performance within all settings.

The states selected for this study have, in most cases, grappled with these shades of meaning, and have refined their criteria to reflect precisely their intent. For example, Kentucky staff clarified student vs. system measures in this way:

Within the 6 rubric dimensions, 5 are strictly system measures. We do need to see that the student is the focus/recipient/participant in those measures but we do not assess the extent to which the actual student performance is demonstrated. It’s got to be there but we don’t look at how much. The 6th dimension, Performance, requires that the student actually demonstrates progress within entries so it is kind of a student measure - although the assessment itself is only used for system accountability, not student (this is the same as for all students in Kentucky, not just students with disabilities - Kentucky has no student accountability in place). The progress is not a measure of how much, but instead a measure of whether progress is documented at all. We don’t ask for a certain amount of progress to move scoring from one level to another. We instead require that the evidence shows progress within certain numbers of entries. (Burdge e-mail correspondence, 2002).

Same Terms with Different Meaning and Multiple Terms Having Similar Meaning

At times we found that scoring definitions or descriptions of gradations of quality for each criterion clarified use of terms in different ways. For example, two states, Arkansas and Kentucky, score on the criterion "performance." By analyzing the rubric gradations of quality, it is apparent that Arkansas is defining performance as evidence of skill to mastery, as demonstrated in multiple settings or on multiple occasions. Kentucky defines performance within the rubric as performance and progress on IEP goals meaningful to current and future environments with products that are age-appropriate. It is not accurate to take just the headings of the rubric criteria and stop there in analyzing what "counts." Thus, in our written and side-by-side analyses, we include all criteria that were headings on the rubric or embedded in the definitions or descriptions of quality gradations and applied in the scoring process. The converse of this is that although Louisiana, Oregon, and Vermont had no criterion labeled "performance," their criteria clearly address similar values to the Arkansas and Kentucky performance criterion. The similar criteria were reflected in terms like skill level, mastery, progress, accuracy, and generalization.

Results: State Side-by-Side Analysis and Criteria Definitions

Given the lessons learned (e.g., articulated, embedded or assumed criteria, overlapping purpose, differences in meaning and multiple terms with the same meaning), we provide a description of scoring criteria used in the five states. These descriptions include actual criteria listed in rubrics, criteria implied in the design of assessment items or format, and additional criteria found in rubric gradations of quality descriptions or described in interviews as having been designed into the alternate assessment items or provided in training. Since we find that the distinction between student and system criteria is blurred at best, we have in some cases defined the same criteria in both ways, and have shown where states use one or both definitions of the criteria. For example, in student criteria we include "Settings when defined as student performing the skills in multiple settings" and in system criteria we include "Settings (multiple) when defined as system offering multiple settings for student." It is not always clear how the scoring process distinguishes between the two, but we have tried to clarify the distinction.

Student criteria identified in at least one state include:

• Accuracy (quantitative, number correct)

• Content standards performance (student performance on standards-based skills or tasks provided by the state)

• Level of assistance (prompts, showing degree of independence)

• Multiple purposes (generalization)

• Mastery

• Performance (qualitative)

• Progress

• Settings (student performance evidence of generalization)

System criteria identified in at least one state include:

• Appropriateness (age, challenge, authenticity, meaningfulness)

• Content standards linkage (teacher developed skills and tasks)

• IEP linkages

• Self-determination (evidence of opportunities for student choice)

• Settings (system provided)

• Social relationships (system provided opportunities)

• Support (access to system provided appropriate supports and technology)

Student Criteria Used Across the Five Sample States

Student criteria used across the five sample states are shown in Table 15. Student scoring criteria reflect actual student performance, and may include a quantitative measure of student accuracy on items reflecting desired knowledge and skills, or a qualitative judgment about the overall level of performance of the student in terms of skills and competence, degree of progress, independence, or ability to generalize. States that included each criterion, and a general definition for each follow Table 15. State by state definitions or justifications for assumed or embedded student criteria are in Appendix B.

Table 15. Student Criteria Used Across the Five Sample States

Accuracy (quantitative) |

X (Extended Academics) |

||||

Content Standards (student performance on

standards-based skills or tasks provided by the state) |

X |

X (Extended Academics – math, reading,

writing; Extended CLRAS – career and life skills standards only) |

|||

Level of assistance (prompts, degree of independence) |

X |

X |

X (CLRAS) |

X |

|

Multiple purposes |

X |

||||

Mastery |

X (part of performance criterion) |

X |

|||

Performance (qualitative) |

X |

X |

|||

Progress |

X (part of performance and support

criteria) |

X (growth model, Extended Academics) |

X |

||

Settings – student performance evidenced |

X (part of performance criterion) |

X |

X (CLRAS) |

X |

General Statements On Use of Student Criteria

All five states have specific student criteria, as defined as either quantitative or qualitative measurement of student performance. None of the states suggested that student criteria were inappropriate for a large-scale assessment. That is in contrast to the discussions of system criteria: systems criteria remain controversial among these states and in the larger testing community. In the traditional pencil and paper tests that are most familiar to us described in the opening section of this report, some states argue that the only criteria measured is student skill and knowledge. Others argue that we can use results from a well-designed traditional test to make some assumptions about what has or has not been taught to a group of students, thus we are measuring the system. For example, if almost all 4th grade students in one school were able to answer test items related to number sense correctly, while almost no 4th grade students in another school could do so, then we can make some assumptions about the opportunities to learn that content in the two schools. The arguments in electing to have system criteria or not generally relate to the discussions states have had with stakeholders on how to define the results of the best possible teaching for students with significant cognitive disabilities, or in other words, how successful outcomes have been defined. The specific student criteria in each state reflect those assumptions and values as well.

Definitions of Student Criteria, Across States

Only one of the sample states, Oregon, specifically includes accuracy as a criterion. For the Oregon extended assessments in reading, mathematics, and writing, the definition of accuracy is quantitative, and is reflected in number correct (or partially correct), reading rate, and reading accuracy. However, one could argue that all of the sample states had same form of accuracy criteria, including Oregon on its Extended CLRAS, with accuracy defined qualitatively using measures such as independent performance of skills, generalization of skills to multiple settings or for different purposes, and appropriateness criterion such as challenge or complexity.

Content Standards Performance (student performance on standards-based skills or tasks provided by the state)