|

A Principled Approach to Accountability Assessments for Students with Disabilities Synthesis Report 70 Martha L. Thurlow, Rachel F. Quenemoen, Sheryl S. Lazarus, Ross E. Moen, Christopher J. Johnstone, Kristi K. Liu, Laurene L. Christensen, Debra A. Albus, Jason Altman December 2008 All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as: Thurlow, M. L.,

Quenemoen, R. F., Lazarus, S. S., Moen,

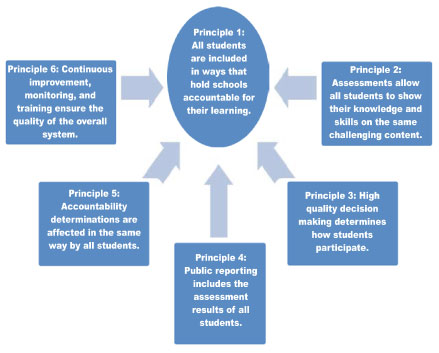

R. E., Johnstone, Table of Contents Acknowledgments The National Center on Educational Outcomes’ Principled Approach to Accountability Assessments was developed in part through review and comment from multiple stakeholders who share the common goal of improving educational outcomes for all students. These valued stakeholders include the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) Research to Practice Panel members who reviewed and gave in-depth comments and who provided research support for the principles. NCEO’s national Technical Work Group provided independent guidance and oversight to our ongoing documentation and research on inclusive practices that form the foundation for the principles. Local educational agency practitioners; parent advocates; state department assessment, general education, and special education staff; state and federal policymakers; and regional and national technical assistance providers who comprise NCEO’s National Advisory Committee provided comments and recommendations for use of these principles in our technical assistance and outreach activities. NCEO’s Community of Practice, comprised of national and regional technical assistance partners, contributed through monthly discussions of inclusive assessment and accountability issues and opportunities. These groups and individuals who provided input and feedback on the principles are identified in the appendix. Each of these valued partners improved this report substantially; any errors remaining are ours. Building on research and practice, the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) has revisited and updated its 2001 document that identified principles and characteristics that underlie inclusive assessment and accountability systems. This report on a principled approach to accountability assessments for students with disabilities reflects what we have learned during the past seven years. The principles provide a vision for an inclusive system of assessments used for system accountability. We address state and district K-12 academic content assessments designed for system accountability and focus specifically on all students with disabilities, including targeted groups of students within this group (e.g., English Language Learners with disabilities). Multiple stakeholders who share the common goal of improving educational outcomes for all students have reviewed and provided comments on the principles and characteristics presented here. This report presents six core principles, each with a brief rationale, and specific characteristics that reflect each principle. The principles are: Principle 1. All students are included in ways that hold schools accountable for their learning. Principle 2. Assessments allow all students to show their knowledge and skills on the same challenging content. Principle 3. High quality decision making determines how students participate. Principle 4. Public reporting includes the assessment results of all students. Principle 5. Accountability determinations are affected in the same way by all students. Principle 6. Continuous improvement, monitoring, and training ensure the quality of the overall system. Several technical assistance tools to support the principles are in development. These include state self-evaluation tools, references for key topic areas, and one-page summaries on each topic covered by the principles. The National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) periodically examines the assessment and accountability context in the U.S. to determine how students with disabilities are included in state implementation. We specifically look at underlying policy assumptions and actions, as well as potential consequences for students with disabilities. We have done this for two decades, and have documentation of our work in reports that are available on the NCEO Web site (www.nceo.info). We believe that it is possible to enhance the positive consequences of assessments used for system accountability with students with disabilities and reduce their negative consequences through systematic attention to assumptions in the design, implementation, and continuous improvement of assessments and related accountability systems. This publication is primarily for audiences in state departments of education, especially for the leadership in assessment and special education offices and their partners who work on large-scale assessments for the purpose of system accountability. This publication is also targeted toward measurement experts who may sit on state technical advisory committees, and the testing contractors who develop large-scale assessments for system accountability. The information in this document is relevant to many others as well, including policymakers, administrators, and parents. We believe that the NCEO principles and their accompanying characteristics are generally consistent with the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing produced by the American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education. Although the NCEO principles do not cover the breadth of issues that the Standards cover, in many ways, they go beyond the Standards because they address more comprehensively the inclusion of students with disabilities. We believe that the NCEO principles also are consistent with the Accessibility Principles for Reading Assessments document developed by the National Accessible Reading Assessment Projects, which focuses exclusively on reading. We last published a set of principles outlining foundational assumptions that support positive consequences of inclusion in assessments in 2001. We have learned much since that time. We examined the research and practice of the past seven years to develop the principles and characteristics in this document. Core resources (i.e., foundational articles from the wider field of large-scale assessment, comprehensive literature reviews, or key policy analyses) from this research and practice base are included at the end of this document. Technical assistance tools to support use of the principles in state level self-evaluation and improvement efforts will be developed. In addition, a comprehensive reference list by key topic areas (universal design of assessments, accommodations, alternate assessment, reporting, and accountability) will be provided. We also will provide one-page summaries of what we know about each of these topics so that the principles are more accessible to multiple audiences. The summaries will target audiences beyond state offices and be suitable for local education agency staff, parents, post-secondary partners, and the general public. There has been a shift in thinking about schools and schooling in the United States—a shift toward high standards for learning for all children, including children with disabilities. National and state policies have made use of the tools of standards-based assessments and accountability systems to push practices for improved achievement, including for students with disabilities, access to the general curriculum based on the same goals and standards as for all other students, and accountability approaches that promote positive results. We have realized that an inclusive system of assessments used for system accountability is one that neither obscures nor discounts what all students really do know and are able to do. The purpose of this document is to provide a vision for such a system. It is a document that states and districts can use in developing and producing a new assessment. It is also a document that states and districts can use in examining their own assessment for use in system accountability, and in thinking about revisions to their system. We use the term "principled" intentionally in the title to communicate that what we are presenting is a view of how things should be in an inclusive system. We provide a set of characteristics for each principle; these characteristics further define what it takes to realize a principle in practice. The principles address state and district K-12 academic content assessments designed for system accountability. Most commonly, these are assessments of reading/English language arts, mathematics, science, social studies, and any other academic content that states or districts might assess on a large-scale basis. The principles specifically address the needs of students with disabilities. Given the increasing linguistic and cultural diversity of the K-12 student population nationwide, any attempt to address the needs of students with disabilities must also specifically address the needs of linguistically and culturally diverse students with disabilities. English Language Learners (ELLs) with disabilities, in particular, are important to include here because they require additional considerations for their inclusion in assessments due to their limited English skills. Although we developed the principles to apply to ELLs with disabilities as well as students with disabilities who are native English speakers, we believe that they apply to many other populations of students as well. Nevertheless, the research basis that we cite, our narrative, and the technical assistance tools reflect our focus on students with disabilities. Underlying the vision in this document is the belief that students with disabilities can and should be expected to achieve the same academic outcomes as their peers without disabilities. In order for that to occur, high quality instruction, access to the general curriculum based on the same curriculum standards as used for typical students, and systematic standards-based formative and summative assessments must be in place to allow these students to achieve in spite of barriers related to disabilities. Our schools must be structured to allow students with disabilities to avoid the barriers that their disabilities create when accessing the curriculum and when demonstrating what they know and can do on assessments. Success in doing so is a critical step on the path toward life-long success. We believe that large-scale assessments can be designed, implemented, and improved over time to ensure high quality measurement of all students’ achievement of state-identified content standards for the purpose of system accountability. Our principles and characteristics describe quality indicators of such assessments. For students to actually achieve at high levels on these assessments, high quality professional development for all teachers and standards-based instruction for all students must be in place. Although high quality professional development and instruction are essential but sometimes neglected components of standards-based reform designed to ensure success for all students, we are focused here on the assessment and accountability systems surrounding standards-based systems. The principles do not address formative assessments, assessments used for progress monitoring, or benchmark testing, unless those assessments have been designed to be used for system accountability, or are being used for system accountability. Similarly, the principles do not specifically address graduation examinations or other promotion examinations, in part because these types of assessment are designed for individual student accountability and require additional considerations. The focus of the principles here is on those assessments used for system accountability (school, district, state), and specifically focuses on all students with disabilities and targeted groups of students within that population. Each principle presented here reflects an essential quality of a good inclusive assessment system. The six principles were developed to reflect best practice as suggested by policy work and research over the past decades. They are not simply a check on compliance with legal requirements, although they generally are consistent with the requirements of current federal laws governing special education and Title I services (i.e., IDEA 2004; NCLB 2001). For each principle, specific characteristics are presented—these provide more precise information about specific elements of the quality identified by the principle. Each of the characteristics also is supported by a rationale statement. The graphic summary of the six core principles (see Figure 1) is meant to be used in conjunction with the more detailed explanations in the text. The graphic shows that Principle 1 is a core goal that is supported by the other five principles, with Principle 6 noting that all the principles are placed in a dynamic system that needs continuous oversight and improvement. The six principles for including students with disabilities in large-scale assessments for system accountability are: Principle 1. All students are included in ways that hold schools accountable for their learning. Principle 2. Assessments allow all students to show their knowledge and skills on the same challenging content. Principle 3. High quality decision making determines how students participate. Principle 4. Public reporting includes the assessment results of all students. Principle 5. Accountability determinations are affected in the same way by all students. Principle 6. Continuous improvement, monitoring, and training ensure the quality of the overall system. Figure 1. Principles for Including Students with Disabilities in Large Scale Assessments for System Accountability

All students are included in large-scale assessments for system accountability in ways that yield defensible inferences about student learning. There is no aspect of the assessment system or the accountability system that excludes a group of students, such as students with disabilities, students who are English language learners, ELLs with disabilities or other students who are highly mobile, disadvantaged, or of minority status. Every student is represented in the assessment system, the reporting system, the accountability system, and school improvement efforts. This principle reflects a belief that all students can be successful when there is systems level commitment to build the capacity for student success in every school and classroom. Including all students in assessment and accountability systems will not ensure their success on its own, but their inclusion can ensure that achievement data include all students before the data are used to target school improvement resources. When fully inclusive assessment systems are developed for system accountability, care is taken to ensure that all students can, in fact, demonstrate their skills and knowledge. This means that policies and practices result in system components that support more accurate inferences for students who have disabilities of all types. Decisions about each system component reflect a deep understanding of varied student characteristics that affect learning as students move toward proficiency in the grade-level content. The validity of the system is assured through assessment and accountability options that specifically address the implications of these varied student learning characteristics. Three characteristics support Principle 1 (see Table 1). Table 1. Principle 1 and Its Characteristics

Characteristic 1.1. All students are included in every aspect of assessment for system accountability. Every aspect of assessment for accountability includes not only full participation of all students in the assessments, but also in the reporting of data, determination of accountability measures, and use of data for school improvement. This characteristic reinforces the need to provide concrete methods of linking performance data reports for all students to the school improvement process, as well as to the accountability processes defined at state and district levels. The state and district provide flexible tools to allow school improvement teams to disaggregate performance data and to answer specific questions about the performance of a subset of students. Special attention is given to ways to disaggregate data within the group of students with disabilities, including aggregating by category of disability and for students with multiple identifiers, such as for ELLs with disabilities. Being able to further break down data by within category of disability (e.g., for students with learning disabilities, specifying nature of the barrier) or by language group for ELLs with disabilities, supports use of data for improvement of assessments and instruction. State and district supports to schools considered in need of improvement include specific strategies designed to increase the performance of students who have not as yet achieved proficiency in the grade-level content. Inclusive systems assure that all students are included in the benefits of such supports.

Inclusive practices start before the development of assessment systems, and continue throughout use of the assessment and accountability systems, with insights and oversight from key stakeholders who have skills and knowledge of academic standards, instructional processes, and understanding about the varied learning needs of all students. Key stakeholders include partners from general education, special education, English as a second language or bilingual education programs, curriculum, assessment and administrative personnel, parents, advocacy groups, related service providers (e.g., speech/language pathologists), and community members as appropriate. Educational professionals across disciplines and stakeholders representing varied student subgroups are essential partners in shaping the development of assessment systems that appropriately address varied learner characteristics in the context of a standards-based approach. They also must be active partners in monitoring the consequences of the assessment systems to ensure continuous improvement. This process will result in assessments that yield more defensible inferences about all students. This collaboration yields improved student outcomes when these partners contribute to all aspects of standards-based systems, not just large-scale assessments for system accountability purposes. Their role includes advising on development and revision of content and achievement standards and systematic alignment of curriculum and instruction to the standards, including ensuring that formative assessments also allow all students to show what they know. These partners can help ensure coherent and aligned standards-based systems that result in improvement of outcomes for all students.

This characteristic ensures that assessment design processes build on understanding how all students learn and show what they know. It requires careful consideration of varied student learning characteristics in the design of assessment options that yield defensible inferences about the learning of all students regardless of their unique needs. This view may require rethinking overall assessment design for fully accessible assessments and the development of improved accommodation policies and alternate assessment options. When innovative methods of assessment for unique learners are considered, care is taken in the application of traditional measurement conventions. When traditional measurement conventions do not match the assessment well, analogous and rigorous technical strategies are implemented to ensure the validity of the assessment.

Assessment systems are designed and developed in ways that allow all students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills on the content and achievement standards for their enrolled grade. This principle indicates that all students with disabilities participate in an assessment system that is appropriately designed and developed to measure enrolled grade-level content, regardless of the nature or severity of their disability or whether they are learning English. Aspects of the system include best practices in the creation of accessible general assessments, including alignment to state standards, flexible approaches to meeting intended constructs, universal design principles, appropriate use of accommodations, and alternate assessments. Four characteristics support Principle 2 (see Table 2). Table 2. Principle 2 and Its Characteristics

The definition of "all" students includes all students who receive educational services in any setting. This includes students in traditional public school placements, and students who change schools or placements, as well as all students receiving federally funded educational services in non-traditional settings such as students in home schools, private schools, charter schools, state-operated programs, in the juvenile justice system, or any other setting where these educational services are provided, with no exceptions because of the nature of disability or specialized services and supports required.

Creating an accessible assessment involves knowledge of needs of the full range of students to be tested along with careful scrutiny of intended constructs and design of assessments. Promising practice for accessible assessments includes reviewing assessments for alignment to standards and universal design elements, disaggregating assessment results at the whole-test and item level, and precisely defining constructs measured on assessments. Accessible assessments are reviewed for adherence to universal design elements, use data-based decision making for the inclusion of particular items (including statistical and qualitative studies on the impact of items on particular populations), and clearly describe what are the intended constructs of items as well as "built in" accommodations students may use (such as defining which items allow calculators for all students). Such transparency in desired student knowledge allows for clear policy and practice about what types of technology, human assistance, or other flexible approaches to assessment will and will not affect the validity of the assessment.

Policies that indicate which changes in testing materials or procedures can be used during assessments, under which conditions, and whether the use of the accommodations or modifications might have implications for scoring or aggregation of scores are set by states. These may change by student characteristic. For example, ELLs with disabilities have access to allowable accommodations for both ELLs and students with disabilities. It is the responsibility of state leaders to gather stakeholders and technical advisors to review the purpose of the assessment and the constructs to be measured, along with available research findings to determine which accommodations allow for valid inferences.

There is a small number of students who require alternate assessments to the general assessment to demonstrate achievement. Data-based strategies are used to determine who the students are who cannot show what they know on the general assessment, why that is the case, and how their instructional opportunities influence assessment decisions. Before alternate assessments are created, states make decisions on how alternate assessment data will aggregate with general assessment data. The end goal of alternate assessments is to serve the need for appropriate measurement of particular students, so that all students are part of the state’s accountability system. Typically students who participate in alternate assessments are those whose disability precludes them from demonstrating knowledge in general assessments under standard conditions or with allowable accommodations. Alternate assessments are used for a very small segment of the population, and are properly designed and implemented.

Decisions about participation and accommodation of students in the assessment system are based on knowledge of student characteristics and needs, combined with knowledge of the goals and purposes of accountability testing. This principle reflects the need for thoughtful decisions about how each student participates in the assessment system. An underlying assumption is the importance of high expectations while ensuring that each student can show what he or she knows and is able to do. Participation decisions are made by the IEP team with full knowledge of the implications of the decision. Established processes ensure that IEP teams have access to training and knowledge needed to make appropriate decisions for these students, regardless of the nature or severity of disability or whether they are learning English. Four characteristics support Principle 3 (see Table 3). Table 3. Principle 3 and Its Characteristics

Historically, students with disabilities were excluded from assessments. As states and districts require that they participate in assessments, it may be tempting to try to protect students, keep them in easy levels of instruction and assessment, or let low expectations guide decisions. These temptations are avoided in an inclusive assessment system. Participation guidelines with decision-making criteria are developed to determine the ways in which individual students participate in the assessment system in order to show what they know. The needs of individual students and the purpose of the assessment are considered when decisions are made.

All students have strengths and needs that result in the different ways they access instruction and assessment. Need is the major determinant of whether accommodations are used with any student (with or without identified disabilities), both for instruction and assessment. Reasonable decisions are made about certain accommodations that are used for instruction but are not appropriate for assessments because they confound the construct being measured. It is possible that some accommodations are appropriate for assessment but not for instruction. For example, a student may need training in how to use a type of technology that is not used for instruction but that enables the student to meaningfully access an assessment

State policies, guidelines, and procedures for assessment participation decision making are developed in collaboration with key stakeholders, are written in plain language that communicates clearly, and are provided to all partners in the decision-making process (IEP teams, 504 teams, English as a Second Language or bilingual education planning partners, or any other stakeholders who contribute to these decisions for any student). There is clear articulation of specific issues that apply to classroom assessment and those that apply to large-scale assessment for accountability, with careful delineation of similarities and differences, and implications of specific decisions for the student and for the school. All of these policies, guidelines, and procedures reflect a commitment that choices being made for each student must promote both access to and high achievement in the student’s enrolled grade curriculum, a curriculum based on grade-specific content and achievement standards. These materials are supported by training designed to meet the needs of all partners, and emphasize the linkage of curriculum, instruction, and assessment. Options for training are flexible and varied to allow all partners—parents, teachers, related service providers, and student as appropriate—to choose formats and schedules that meet the student’s needs.

Decisions about participation in one particular state or district assessment may be different from decisions about participation for another assessment that has a different purpose or different format. The membership of every IEP team includes people who know the student and are in the best position to understand the issues that affect assessment for that student. An English as a Second language or bilingual education teacher plays a key role in making decisions for ELLs with disabilities. Parents and the student, when appropriate, are essential members of the team. Additionally, there may be other people not typically on the IEP team who have insight into the student’s needs; they should be consulted about decisions as well. These people may include the student (if the student is not already participating on the team), paraprofessional, counselor, psychologist, caretaker, and others. Participation decisions made by the IEP team for each state and district assessment, and the team’s rationale for the decisions, are made year by year, or more frequently if needed. IEP documentation of these decisions provides an important record of the individual student’s needs and strengths. These decisions are reviewed and changed as appropriate with the development of each annual IEP to reflect changing student needs and skills, and to reflect changes in the assessment system. Although IEPs often are developed all year on a schedule that may not coincide with planning for state and district assessments, decisions are made at the IEP meeting that most closely precedes each assessment so that the most appropriate decisions are made.

Principle 4. Public reporting includes the assessment results of all students. Public reporting is the first level of accountability for the results of students with disabilities. The philosophy underlying this principle is that every student counts and in a well-functioning system, the system itself is held accountable for every student. This philosophy is reflected through the inclusion of student results in public reports. Regardless of how students with disabilities are assessed—with or without accommodations, with a native language version, or in an alternate assessment—their results are reported. If their results are not reported due to technical adequacy issues (for example, the student used a testing modification), or due to issues with the testing company handling of tests, or due to student absence, or for some other reason, all students’ participation are still accounted for in the reporting system. A well-functioning system is flexible and allows for further disaggregation so that groups of students with multiple identifiers, such as ELLs with disabilities, are clearly reported. Although the focus here is on public reporting, it is assumed that these characteristics apply as well to reporting that occurs internal to a state or district, and certainly applies to required reporting of districts to states, and of states to the federal government. Five characteristics support Principle 4 (see Table 4). Table 4. Principle 4 and Its Characteristics

Every student is counted. The basis for the counting of students is student enrollment. For students who are receiving special education services, the child count at a time closest to the time the assessment is administered typically is the basis for the count of all students. "All students" includes not only students in traditional public school placements, but also students who change schools or placements. All students who receive federally funded educational services in non-traditional settings are included and reported as well. These students include those in home schools, private schools, charter schools, state-operated programs, and in the juvenile justice system. The challenge of counting every student regardless of the severity of disability, and ensuring that each student’s progress counts, is fundamental to the success of standards-based reform. There is a national consensus that all students are to be held to high standards and all schools are to fully support all students’ efforts to reach those standards, regardless of the setting. If some students are excluded or set aside in reporting, the public has no way of knowing how all students or all schools are doing. This characteristic also means that every student counts, even if the student received an assessment result that could not be aggregated, was exempted by a parent, or did not count as a participant because of the use of a modification during testing. Despite the unfavorable outcomes that resulted from these conditions, the student still is part of the population and counts in the denominator when percentages of students assessed are calculated. Just as the IEP enrollment for the school is the denominator when participation rates and proficiency rates of students with disabilities are calculated at the school level, and the IEP enrollment for the district is the denominator when participation rates and proficiency rates of students with disabilities are calculated at the district level, so too does the state IEP enrollment become the denominator when state participation rates and proficiency rates of students with disabilities are calculated for the state. Without a stable and consistent denominator, the results of some students are lost, and the participation and performance results become confusing at best and incomprehensible or misleading at worst.

The reporting of the number and percentage of students assessed and not assessed, and the reporting of data on performance, by type of assessment, are provided as often as those data are reported for students without disabilities. This process includes specific reports of how many ELLs with disabilities participated (and did not participate) and their performance. All of these pieces of information are arranged in ways that are similar to those used for students without disabilities, and are provided as often as they are for students without disabilities. The goal is to ensure that public reporting is transparent and accessible for students with disabilities, just as much as it is for other students. Those reading public reports will better understand in this way that students with disabilities are not a group whose information and results are being hidden, but rather the system is checking on how these students are faring so that they are not overlooked as they were in the past.

At a minimum, every student who is not actually assessed in the assessment system is detectable when results are reported. Typically, this identification is done by reporting the number of students not participating in the assessment system. Even if a state or district factors students who do not take the assessment into the reported results (e.g., by giving them a zero), the number of students excluded from participation is still reported. In addition, the reasons for exclusion (e.g., parent request, absenteeism, ELL exemption, noncompliance, cheating, procedural errors such as nonscorable test protocols due to administration or test company errors) are reported for students with disabilities. This characteristic does not preclude appropriate respect for confidentiality of individuals. For example, if reporting information on reasons for exclusion at the school level violates confidentiality, then the information is reported at the district level. If confidentiality is violated because a state is reporting information by disability category, then the information on reasons for exclusion is reported only at the subgroup level (rather than by disability category). Regardless of where the confidentiality issue arises —if one does—there are clear indications of where the information on students not assessed, or whose results cannot be aggregated, are revealed in public reports. Further, explanations are given of the reasons for why results can not be reported.

When there are questions about a policy, such as when an accommodation is allowed even though its effects on the validity of results have not been determined, the results of the use of the accommodation are as transparent as possible. Policy decisions about accommodations or other administration considerations often must be made when the research literature is mixed in its evidence. Thus, policy decisions are made even though policy questions may remain. Accommodations frequently give rise to these policy questions. It may be determined, for example, that the use of a scribe is appropriate, but that there are questions about the use of the accommodation and whether it really is appropriate to aggregate results when the accommodation is used. There may be a belief that it should be used by a limited number of students, and a concern that if using such an accommodation is allowed the number of students using the accommodation will increase dramatically to the point that it is being used by students for whom the accommodation is inappropriate. In this situation, even though the policy decision has been to allow the accommodation and aggregate the results—the results are also disaggregated so that they can be publicly examined and discussed.

State and district staff members have a responsibility to ensure that data are used in ways that are consistent with the purpose of each assessment. Reports are readily available and accessible, and include cautions about misinterpretation of data. Particular care is taken to ensure that reports are available and accessible to linguistically and culturally diverse parents. This task entails making information available in hard copy and a variety of formats and languages. States and districts provide assistance interpreting the results. If tests are designed to yield the most accurate data at the classroom or school level, all student level reports will specify the necessity of using data from multiple sources (e.g., from classroom assessments or specific diagnostic tools) for individual students. Consideration is given to having community information sessions or special outreach to the media to help people use the reports responsibly. This process may be especially important when there are new approaches to data, such as growth models for accountability, where it may be more difficult to include students with disabilities because of high mobility. Clear reporting of these issues, including when students are lost to inclusion in the data reports because of mobility, and the characteristics of those students who are dropped, is part of public reporting. Finally, for students in placements other than the local school, students are included in reports that will most directly affect the student’s education—where his or her performance counts, and where public reporting can make a difference. For example, if a student with disabilities is being served in a specialized setting outside of his or her home district (or school), the progress of that student is reported in the context where accountability and concern for that student most directly lies, in other words, in the student’s home school (the school that the student would have attended if he or she did not have a disability).

This principle provides the second level of accountability for students with disabilities, that of school, district, and state accountability. State accountability plans that promote equal access and opportunity for all students and increased expectations for schools ensure that assessment participation and performance data are integrated into district and state accountability determinations in the same way for all students. Three characteristics support Principle 5 (see Table 5). Table 5. Principle 5 and Its Characteristics

Characteristic 5.1. Performance data for all students factor into accountability determinations regardless of how they were assessed or why they were not assessed. All assessment results that can be validly aggregated contribute in a similar way to accountability determinations regardless of how students were assessed. Using assessment practices such as accommodations or alternate assessments that the state has determined to be valid for this use does not diminish the impact students’ results have on accountability determinations. Students who have assessment results that cannot be aggregated or who have no assessment results are also included in accountability determinations. The reasons students lack results that can be aggregated are reported and examined in ways that promote increasing the percentage of results that can be aggregated.

Accountability plans are based on the same assumptions for all groups and eliminate any implementation guidelines that systematically exclude or reduce the impact of some groups. Practices that run the risk of doing this by making low group performance invisible or acceptable are rejected, such as adjusting target performance for group characteristics or looking only at changes in test performance. Low group performance remains visible by avoiding arbitrarily large minimum group size reporting requirements or by using average scores or various kinds of indices. Decisions about procedures proposed to protect the privacy of the students and to produce sound accountability decisions are subjected to independent review for technical adequacy to ensure that states, districts, and schools are transparent in their performance and provide for all students to affect accountability determinations equitably.

Accountability reports show results broken out by student groups, grade levels, content areas, districts, and schools. District and school information shows how student performance relates to the opportunities students have to learn the challenging grade-level content, and the training, resources, state improvement plans and activities, and other supports available for these schools, teachers, and students. States support, train, and expect educators at all levels to respond to accountability reports by accelerating and scaffolding student learning to improve access of every learner to the grade-level content. Reports that merely identify groups of low performing students and that are presented without support for effective use for school improvement could lead to blaming and excuse-making that hinders progress toward the goal of success for all students.

Principle 6. Continuous improvement, monitoring, and training ensure the quality of the overall system. The value of the assessment system is documented and strengthened over time through continuous monitoring, training, and adjustments in all aspects of the assessment and accountability system. This principle addresses the need to base inclusive assessment practices on current and emerging research and best practice, with continuous improvement of practices as research-based understanding evolves. Because society is expecting more of traditional large-scale assessments and requiring multiple uses of test results, we must invest time and thought into improving them. It requires addressing potential threats to validity from the design of the assessment, development of participation guidelines and training, administration procedures, and monitoring of implementation practices. By working together on improvement of inclusive large-scale assessments for system accountability, stakeholders can sustain commitment to keeping the standards high and keeping the focus clear on all students being successful. Ongoing training of IEP team members and other key partners is an essential component of this effort. Four characteristics support Principle 6 (see Table 6). Table 6. Principle 6 and Its Characteristics

Characteristic 6.1. The quality, implementation, and consequences of student participation decisions are monitored and analyzed, and the data are used to evaluate and improve the quality of the assessment process at the school, district, and state levels. Identifying methods to use at the school level to check on decision-making patterns, and providing feedback to IEP teams on appropriateness of decisions, improves the quality of assessment data in the long term. Likewise, if good participation, accommodation, and alternate assessment decisions are made at the IEP team level, but the information is poorly documented, not communicated to instructional settings or to assessment personnel, the validity of the assessment results may be affected. By monitoring these decisions, and ensuring the decisions are implemented appropriately, schools, districts, and states ensure the best possible measurement of actual student progress toward standards. Across the state, test administration procedures and forms capture essential data for determining the characteristics of students, accommodations used by the student for some or all parts of the test, or ways the student was included in alternate assessments. Capturing data of student characteristics and use of accommodations for all or parts of the test yield essential data in determining the validity of the test for these students specifically, and contribute to the research base on effects of accommodations on the validity of the results more generally. Understanding the characteristics of students who participate in alternate assessment options assists in validation of the assessment approach for the participants, as a group and as individuals, and in identification of a need for adjustment of the approach. It also provides a statewide profile of patterns of decision making and use of participation options and leads to systematic intervention with schools where unusual patterns of participation are occurring. In developing systems, the view of consequences often depends on the perspective of the viewer. For that reason, the ongoing monitoring and evaluation of consequences requires stakeholder involvement to determine which consequences are intended or unintended, and which are positive or negative. A systematic process for consequential validity studies is built into state procedures, which builds support for changes in the systems as they are needed.

All IEP teams and other key personnel have access to ongoing training and technical assistance. State departments of education make connections, provide leadership and incentives, develop written materials, and present introductory workshops, but day-to-day support is built into a district’s comprehensive system of professional development. In addition, states partner with institutions of higher learning to rethink basic teacher competency and licensure requirements in light of the new emphasis on measuring the progress of all students toward high standards. Parent training organizations and other advocacy groups are essential training partners to reach parents and the students themselves. Increasing the assessment literacy of IEP team members improves the quality of the assessment decisions made by each team. Increased assessment literacy, in turn, improves how well assessments measure progress toward standards for all students, regardless of how they participate (with or without accommodations, or in an alternate assessment). Ultimately, the validity of the assessment results for use in system accountability rests on these individual student participation decisions.

Information is gathered from districts and schools indicating how reports have been used and what actions have been taken in response to reports. Such information is reviewed when new test results are obtained and it is related to the performance of students with disabilities. Evaluations of educators’ responses to the accountability reports and decisions and their impact on student learning are used to determine what additional staff development or supports or other changes in the accountability system may be needed to continue improving student learning.

States monitor how schools implement assessments and how they use and respond to assessment results to see where assessment practices and tools need to be improved. States also remain informed about federal requirements, guidance, and options. States seek solutions to improving assessment tools and practices by working with other states and with experts in the fields of assessment, curriculum and instruction, and special populations. Note: The National Center on Educational Outcomes has been documenting the participation and performance of students with disabilities in large-scale assessments for almost two decades. Over that time span, we have published results of data analyses, policy analyses, and systematically documented changing practices of inclusive assessment. The Principles reflect the extensive bibliographies of our publications over the time period. The list below was chosen to reflect key references that have been commonly included in our publications, focusing on seminal works on large-scale assessment, public policy on standards-based reform, testing, and students with disabilities, literature reviews, and specific NCEO publications that summarize key issues that are addressed in the Principles. This list is not exhaustive, but reflects a core body of work that has influenced our thinking. We will continue to update core references in our Web version of the Principles as we develop and publish companion resources for these Principles. AERA, APA, & NCME (1999). Standards for educational and psychological testing: Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association. Albus, D. A., & Thurlow, M. L. (2007). English language learners with disabilities in state English language proficiency assessments: A review of state accommodation policies (Synthesis Report 66). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Bolt, S. E., & Roach, A. T. (2008). Inclusive assessment and accountability: A guide to accommodations for students with diverse needs (The Guilford Practical Intervention in Schools Series). New York, NY: Guilford Publications, Inc. Bolt, S. E., & Thurlow, M. L. (2004). Five of the most frequently allowed testing accommodations in state policy. Remedial and Special Education 25 (3), 141-152. Browder, D. M., Wakeman, S. Y., Flowers, C., Rickelman, R., Pugalee. D., & Karvonen, M. (2007). Creating access to the general curriculum with links to grade level content for students with significant cognitive disabilities: An explication of the concept. Journal of Special Education, 41(1), 2-16. Christensen, L. L., Lazarus, S. S., Crone, M., & Thurlow, M. L. (2008). 2007 state policies on assessment participation and accommodations for students with disabilities (Synthesis Report 69). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. DeStefano, L., Shriner, J. G., & Lloyd C. (2001). Teacher decision making in participation of students with disabilities in large-scale assessment. Exceptional Children, 68(1), 7-22. Fast, E. F., Blank, R. K., Potts, A., & Williams, A. (2002). A guide to effective accountability reporting. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers. Haertel, E. H. (1999). Validity arguments for high stakes testing: In search of the evidence. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices, 18(4), 5-9. Heubert, J. P., & Hauser, R. M. (1999). High stakes: Testing for tracking, promotion, and graduation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Johnstone, C. J., Altman, J., Thurlow, M. L., & Thompson, S. J. (2006). A summary of research on the effects of test accommodations: 2002 through 2004 (Technical Report 45). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Kane, M. (2002). Validating high-stakes testing programs. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices, 21(1), 31-41. Kane, M. (2006). Validation. In R. L. Brennan (Ed). Educational measurement (4th edition). Washington, DC: American Council on Education/Praeger. Kleinert, H., Browder, D., & Towles-Reeves, E. (2005). The assessment triangle and students with significant cognitive disabilities: Models of student cognition. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, National Alternate Assessment Center. Lane, S., Park, C. S., & Stone, C. (1998). A framework for evaluating the consequences of assessment programs. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices, 17(2), 24-28. Lazarus, S.S., Thurlow, M.L., Lail, K.E., & Christensen, L. (2008). A longitudinal analysis of state accommodations policies: Twelve years of change 1993-2005. Journal of Special Education. Sage Journal Online First published May 12 at: http://sed.sagepub.com/cgi/rapidpdf/0022466907313524v1; Hard copy: forthcoming, will be in 43(2). Marion, S., & Pellegrino, J. (2006). A validity framework for evaluating the technical quality of alternate assessments. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 25(4), 47-57. McDonnell, L. M.,

McLaughlin, M. J., & Morison, P. (1997).

Educating one and all: Students with

disabilities and standards-based reform.

National Academy Press, Washington D. C.

McGrew, K. S., & Evans, J. (2004). Expectations for students with cognitive disabilities: Is the cup half empty or half full? Can the cup flow over? (Synthesis Report 55). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.McLaughlin, M. J., & Thurlow, M. L. (2003). Educational accountability and students with disabilities: Issues and challenges. Educational Policy, 17(4), 431–451. Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd edition). Washington, DC: American Council on Education. Messick, S. (1995). Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. American Psychologist, 50(9), 741–749. Messick, S. (1989). Meaning and values in test validation: the science and ethics of assessment. Educational Researcher, 18, 5-11. National Research Council. (2004). Keeping score for all: The effects of inclusion and accommodation policies on large-scale educational assessments. Judith A. Koenig and Lyle F. Bachman, (Eds). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. National Research Council. (1999). Testing, teaching, and learning: A guide for states and school districts. (Committee on Title I Testing and Assessment, R. F. Elmore & R. Rothman, eds). Board on Testing and Assessment, Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Nolet, V., & McLaughlin, M. (2005). Accessing the general curriculum: Including students with disabilities in standards-based reform (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc. Office of Special Education Programs. (2006). Tool kit on teaching and assessing students with disabilities. Washington DC: US Department of Education. Retrieved September 1, 2006 from http://www.osepideasthatwork.org/toolkit/index.asp. Pellegrino, J. W., Chudowsky, N., & Glaser, R. (2001). Knowing what students know: The science and design of educational assessment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Quenemoen, R. (2008). A brief history of alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards (Synthesis Report 68). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Shriner, J. G., & DeStefano, L. (2003). Participation and accommodation in state assessments: The role of individualized education programs. Exceptional Children 69(2), 147-161.Sireci, S.G., Scarpati, S., & Li, S. (2005). Test accommodations for students with disabilities: An analysis of the interaction hypothesis. Review of Educational Research 75(4), 457-490. Thompson, S., Blount, A., & Thurlow, M. (2002). A summary of research on the effects of test accommodations: 1999 through 2001 (Technical Report 34). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Thompson, S. J., Johnstone, C. J., & Thurlow, M. L. (2002). Universal design applied to large scale assessments (Synthesis Report 44). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Thompson, S. J., Thurlow, M. L. & Malouf, D. (2004, May). Creating better tests for everyone through universally designed assessments. Journal of Applied Testing Technology, http://www .testpublishers.org/atp.journal.htm. Thurlow, M. L., Barrera, M., & Zamora-Duran, G. (2006). School leaders taking responsibility for English language learners with disabilities, Journal of Special Education Leadership 19(1), 3-10. Thurlow, M. L., Elliott, J. L., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2003). Testing students with disabilities: Practical strategies for complying with district and state requirements (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc. Thurlow, M., Quenemoen, R., Thompson, S., & Lehr, C. (2001). Principles and characteristics of inclusive assessment and accountability systems (Synthesis Report 40). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Thurlow, M. L., Thompson, S. J., & Lazarus, S. S. (2006). Considerations for the administration of tests to special needs students: Accommodations, modifications, and more. In S.M. Downing & T. M. Haladyna (Eds.), Handbook of test development (pp. 653-673). Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum. Thurlow, M. L., Ysseldyke, J. E., & Silverstein, B. (1995). Testing accommodations for students with disabilities. Remedial and Special Education 16 (5), 260-270 Tindal, G., & Fuchs, L. (1999). A summary of research on test changes: An empirical basis for defining accommodations. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, Mid-South Regional Resource Center. Zenisky, A., & Sireci, S. (2007): A summary of the research of the effects of test accommodations: 2005 through 2006 (Technical Report 47). Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Zlatos, B. (1994). Don’t test, don’t tell: Is "academic red-shirting" skewing the way we rank our schools? The American School Board Journal, 191 (11), 24–28. Groups and Individuals who Provided Review and Comment during Development of the 2008 NCEO Principles NCEO Research to Practice Panel Marsha Brauen, Director of WESTAT Candace Cortiella, Director of the Advocacy Institute Claudia Flowers, Associate Professor of Educational Research and Statistics, University of North Carolina at Charlotte Brian Gong, Co-founder and Executive Director of the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment, Inc. (NCIEA) Harold Kleinert, Executive Director of the Interdisciplinary Human Development Institute at the University of Kentucky, and co Director of the National Alternate Assessment Center (NAAC) Margaret McLaughlin, Professor in the Department of Special Education at the University of Maryland at College Park and the Associate Director of the Institute for the Study of Exceptional Children and Youth James Shriner, Associate Professor of Special Education at the University of Illinois at Urbana Stephen G. Sireci, Professor in the Research and Evaluation Methods Program and Director of the Center for the Educational Assessment in the School of Education at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst NCEO Technical Work Group Diane Browder, Professor of Special Education, University of North Carolina, Charlotte Ron Hambleton, Professor of Education and Psychology and Chairperson of the Research and Evaluation Methods Program, University of Massachusetts, Amherst Michael Kolen, Professor, Educational Measurement and Statistics, University of Iowa Suzanne Lane, Professor of Psychology in Education, University of Pittsburgh Mary Ann Snider, Director of Office of Assessment & Accountability. Rhode Island Department of Education Jerry Tindal, Professor of Educational Leadership, University of Oregon NCEO National Advisory Committee Paul Ban, Director of Special Education for the Hawaii Department of Education Melissa Fincher, Director of Assessment Research and Development for the Georgia Department of Education Geno Flores, Chief Academic Officer of Prince George’s County Public Schools, Maryland Connie Hawkins, Executive Director of the Exceptional Children’s Assistance Center (ECAC) Elizabeth Kozleski, Director of the National Institute for Urban School Improvement (NIUSI) Bruce Rameriz, Executive Director for the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) James H. Wendorf, Executive Director for the National Center for Learning Disabilities (NCLD) Markay Winston, Director of Student Services for the Cincinnati Public Schools

NCEO Inclusive Assessment and Accountability Community of Practice Organizational Members Assessment and Accountability Comprehensive Center Council of Chief State School Officers National Alternate Assessment Center National Association of State Directors of Special Education National Association of State Title I Directors Regional Resource and Federal Center Program Federal Resource Center Mid-South Regional Resource Center Mountain Plains Regional Resource Center North Central Regional Resource Center Northeast Regional Resource Center Southeast Regional Resource Center Western Regional Resource Center Partners from the Office of Special Education Programs and the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education at the United States Department of Education |

||||||